Why your favorite café might soon close for good – unless it radically changes its business model.

When I was a little girl, my father told me that the scissors between rich and poor would widen drastically during my lifetime. I still remember sitting on his pull-out sofa in the cramped attic room of the retirement home where he worked. He had turned barely sixteen square meters into a full apartment – hallway, kitchen, dining nook, even a “living room” area. It was modest, yet cozy.

At the time, I didn’t understand what he meant. Thirty years later, I do. His words echo every time I see small, local businesses – like the cafés we love – struggling to survive while the big players grow richer and more powerful.

Why local and human economies are falling behind

I never questioned GDP. I accepted it at face value: 2–3% growth per year sounded normal. Small, almost negligible. But of course, that’s exponential growth: the economy grows 2–3% on top of the previous year, which means it doubles in size every twenty-three years, then doubles again.

Here’s the problem: you, me, and your favorite café all have the same twenty-four hours in a day. We can’t (and don’t want to) spend them all working. If endless growth is the goal, the system shifts its focus to where growth is possible – and that’s not human labor.

GDP (Gross Domestic Product) simply measures the sum of all final goods and services in a country. It makes no distinction between good or bad, meaningful or destructive. A natural disaster like the Ahrtal flood of 2021 actually boosts GDP, because rebuilding counts as “growth.”

And in this system, anything that can increase productivity through technology automatically becomes more valuable than work that cannot scale. A healthcare worker, for example, is often more effective when they slow down – but GDP rewards only speed and volume. If the economy must grow 2–3% each year, then in theory a nurse would have to be twice as “productive” in twenty-three years. Which is, of course, impossible. I saw my father struggle with this all his life. He eventually started a home caring business for elderly people and I’m sad to report that his business model was doomed to fail, which now I know wasn’t his fault.

The startup and real estate hype that’s slowly killing your favorite places

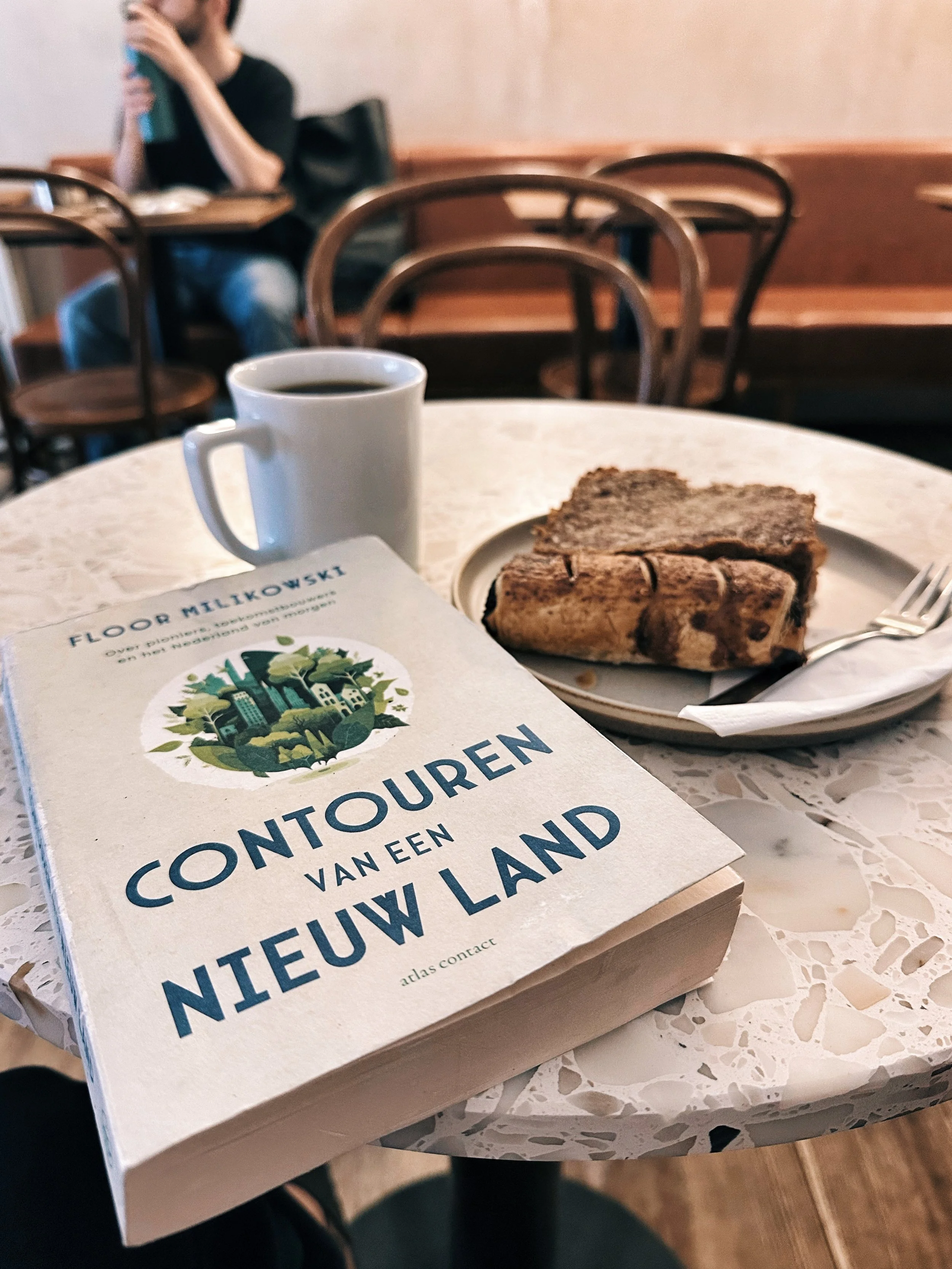

When I first moved to Berlin more than twelve years ago, the café and restaurant scene was booming. Coffee was a little over €2, and you could buy lunch for €5. The startup scene was negligible; there was no real money in it yet. My rent for a room in a shared flat in Friedrichshain was just €205. From today’s perspective, it was very bohemian.

Now, everything looks different. The startup scene has exploded and inflated the salaries of some – but not all. International real estate investors took note, buying up property across the city. Berlin, which made international headlines as a hip, affordable destination, drew hundreds of thousands of newcomers in just a decade. This development reshaped the city’s economic landscape – for businesses and residents alike – but not everyone benefited from the boom.

Over the past few decades, the most profitable businesses have shifted dramatically. For much of the 20th century, the backbone of the economy was companies employing tens of thousands of skilled workers. Today, the stars are digital platforms, AI firms, and tech startups – companies with maybe a few thousand employees, sometimes far fewer, yet the ability to scale exponentially.

For a café, the opposite is true. Popularity means hiring more staff, more labor, more costs. It cannot scale without limits. As machines and algorithms take over tasks once done by humans, the value of human labor decreases – and with it, the value of businesses that depend on human presence, That’s why there’s a sudden hype of the newly launched LAP. The people that hype the model have understood where we’re headed.

We now live in an age where ownership of capital assets – machines, algorithms, real estate – drives wealth. Those without such assets are left behind, relying only on their ability to provide human labor. And if your customer base is mostly those “ordinary mortals,” you’re stuck: they’re the very people pinching pennies, cutting down on coffees and lunches. Rising costs meet shrinking disposable income. It’s a zero-sum game. I could cry!

The value paradox

Lauren Hom, a NYC-based illustrator and chef I interviewed for my book Work Trips and Road Trips, put it bluntly: as long as she makes more money creating content about cooking than by actually cooking, she’ll choose content production. What she’s really selling is her brand and the “real estate” of her social media presence, not the food itself.

I didn’t think much of that statement at first. But after working with several hospitality businesses, I realized two things:

A) they all face the same challenge, and

B) they won’t survive with a purely “old-school” hospitality model.

To make it, they’ll need to diversify – capitalize on their brand, their physical space, and ideally create scalable revenue streams. In today’s attention economy, that means leveraging online audiences and reimagining their venues as multi-use spaces. Partnerships with asset-driven businesses, brand collaborations, creative rentals – these are the strategies that keep them afloat.

What does it leave us with?!

So if your favorite café closes, it won’t be because the coffee isn’t good enough or the staff isn’t friendly. It will be because the rules of the economic game have changed. In a world where value is measured by scalability and asset ownership, labor-heavy businesses are playing a game they can’t win. The path ahead for them is set yet likely not clear to all of them just yet: either reinvent themselves by treating their brand, space, and audience as assets – or slowly get priced out of existence.

Your morning cappuccino, in other words, is no longer just about beans and milk. It’s about whether a local business can find a place in an economy that rewards algorithms over humans, and capital over community.